Shout out to our comrade Bypolar, aka the Toxic Cherub. He’s been crafting some unique hip hop, narrating the struggle with prophetic rhetoric. From (mis)education in the Seattle public schools, through Malcolm-style self-education in prison, he’s developed his own unique style of intervention and reflection on the movements that have shook our city’s streets the past few years. Check out his track “Picture Frame”, and look out for his upcoming mixtape:

How to Overthrow the Illuminati (Theory)

24 Oct Teaching in the ‘hood, I hear a lot about the Illuminati. Some of my smartest students are hardcore conspiracy theorists, and they are quite good at preaching about the Illuminati, a secret group of elites who supposedly control the world. When we get into dynamic class discussions about police brutality, about the economic crisis, or about hip hop, someone will inevitably bring up the Illuminati as an explanation for why Black people are oppressed, for why politicians or hip hop artists mislead people, or for why society increasingly seems like it’s on the verge of breaking down.

Teaching in the ‘hood, I hear a lot about the Illuminati. Some of my smartest students are hardcore conspiracy theorists, and they are quite good at preaching about the Illuminati, a secret group of elites who supposedly control the world. When we get into dynamic class discussions about police brutality, about the economic crisis, or about hip hop, someone will inevitably bring up the Illuminati as an explanation for why Black people are oppressed, for why politicians or hip hop artists mislead people, or for why society increasingly seems like it’s on the verge of breaking down.

My friends and I wrote this pamphlet to engage with these young intellectuals. We argue against the Illuminati conspiracy theory, but we do so in a way that aims to engage with the questions these folks are trying to answer, instead of patronizingly dismissing them as ignorant:

My friends and I wrote this pamphlet to engage with these young intellectuals. We argue against the Illuminati conspiracy theory, but we do so in a way that aims to engage with the questions these folks are trying to answer, instead of patronizingly dismissing them as ignorant:

Illuminati theory helps oppressed people to explain our experiences in the hood. Society throws horrible stuff in our faces: our family members get locked up for bullshit. Our friends kill each other over beefs, money or turf. Our future is full of dead-end jobs that don’t pay shit. We struggle to pay bills while others live in luxury. On TV, we see people all over the world dying in poverty, even though we live in the most materially abundant society in history. Most people act like none of these terrible things are happening. Why does this occur? We start looking for answers, and Illuminati theory provides one.

We believe Illuminati theory is wrong, and we wrote this pamphlet to offer a different answer. We wrote this pamphlet because we know people who think about the Illuminati usually want to stop oppression and exploitation. They’re some of the smartest people in the hood today. Forty years ago, Illuminati theorists would’ve been in the Black Panther Party. Today most of them sit around and talk endlessly about conspiracies. This is a waste of talent.

I am sharing this pamphlet mostly to reach any youth reading this blog. For teachers reading this, I also wonder whether it might be useful in the classroom? I imagine if you teach a lesson on the Illuminati theory, your students will probably be engaged and interested since many of them are studying this stuff already on their own. I’m not sure if you can get away with assigning this pamphlet as part of such a lesson; it may be too direct and too radical for most schools. But at the very least, I hope it can serve as a reference to help get you started.

In any case, I will cover the printing costs of a class set of pamphlets for the first person who manages to teach this text in a school classroom. I will do the same for the first person who convinces your colleagues and administrators that teaching it aligns with the new Common Core standards we are required to teach. If you do that, send me your lesson plan, and we can post it here so others can use it.

We tried as hard as possible to make the pamphlet a considerate text, meaning we define key vocabulary within the narrative, or in the glossary, and attempt to break down complex social theories in everyday language, with references to daily life experiences. The intended audience is not necessarily all youth; it is written for intellectuals in the ‘hood who are already interested in the Illuminati, so it presumes some level of prior knowledge. But it is intentionally written in a non-academic way with as little jargon as possible.

We are trying to reach intellectuals in the ‘hood because we think they could have a tremendous impact on the world if they end up catalyzing social movements, but their conspiracy theories are holding them back. Also, we see many of these young intellectuals dealing with similar problems that older intellectuals and activists are dealing with; they are asking “why do more people around me not see what’s wrong with our society? If they do see it, why aren’t they willing to take action to change it”?

Many academics and activists answer these questions by suggesting that they are the only enlightened ones, destined to teach others who are too blinded by false consciousness, too brainwashed by the media, by their privilege, or by their religion. Young intellectuals in the ‘hood develop an analogous explanation when they say they are the only ones who are not fooled by the Illuminati’s lies. These elitist reactions to our alienation fail to help us overcome it, and fail to explain why more people are not fighting back, and how this might change; instead, they simply widen the gap between the intellectuals and everyone else.

We need a theory we can use to overcome this alienation, to catalyze the processes through which we all fight back together. Conspiracy theories are a roadblock in the way of this.

I am confident that some of my students will overcome his roadblock and will come up with new explanations for their social oppression, and creative strategies for overcoming it.

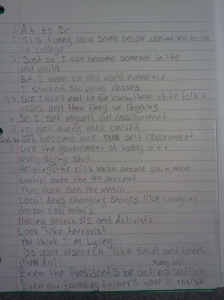

“I set myself an assignment, to get every race united”

28 JunThis poem was written by one of my students, and I am sharing it with his permission. He self-identifies as indigenous, from Oaxaca and South Park. In this poem, he talks about how school reproduces white supremacy, and concludes that in order to stop this he needs to set himself an assignment, to unite the races against the system, replacing the rich white people’s state apparatus with multi-racial “self-government”.

In my experience, this poem is a solid representation of a growing anti-racist and anti-capitalist philosophical tendency among the youth I work with, most of whom have dropped out or fallen behind in school. I have met dozens of students like this author, who are tired of the Eurocentric curriculum, high stakes testing, and discipline of the schools. They say these exist only to prepare them for non-existent jobs or mountains of college debt they will never pay back.

They say they are tired of the beef (conflicts) that high school concentrates, where the classrooms become like prison yards dividing and conquering Blacks vs. Mexicans vs. Natives, with the help of police who instigate this violence in the name of controlling gangs. They are also struggling to create an intellectual milieu of thinkers who are willing to learn from each other, through hip hop, independent social media, some critical engagement with anarchist and communist revolutionary literature, and social movements like Occupy, anti-police brutality protests, etc. At times, this intellectual tendency is expressed as criticism of current events (such as the Seattle media’s portrayal of May Day protestors mentioned in this poem), and other times it is expressed as conspiracy theories about the Illuminati (which can go in either left wing or right wing directions).

While some teachers and other adults may dismiss this author because of his stridency, his “slang”, or his spelling errors, they would be missing out on a chance to understand the frustrations, the ideas, and the desires of one of the people who will be most likely to create movements that will shake this society to it’s core.

I also want to mention that some of the students who reject and criticize school also defend their schools from budget cuts and other neoliberal attacks; students have walked out on this basis across the country. Some have emphasized they want some stability in their lives, and are looking for this in classrooms which they don’t want disrupted by school closings and repeated teacher layoffs and transfers. Isn’t it possible to desire this stability while still rebelling against the control and conformity that come along with it under the current system?

In any case, if these youth can manage to create ways to learn and “do their research” together as this poem says, they just may be able to develop the theories and strategies necessary to start a movement. And that movement might flow back into the classrooms, shaking up the education system in some necessary ways. It just might infuse classroom discussions with a defribulator’s voltage of critical, social creativity and self-government – enough to break through the schools’ control systems, creating more freedom for all of us.

Reading for Revolution (Parts 1 and 2)

26 JunI recently wrote two articles on struggles for critical literacy, which I posted over on the Black Orchid Collective blog. These are part of a 3 part series called “Reading for Revolution”. The first article, “Steal the Ability to Read this Book”, makes a case for seizing the reading skills that slave-masters and capitalist bosses have systematically denied oppressed communities. It also highlights the importance of literacy in revolutionary movements historically and today:

There is a reason why the slave masters made it illegal for slaves to learn to read. In the hands of oppressed people, written words can be revolutionary. They were back then, and they still are today.

Of course, the written word would not be powerful without the spoken word. Spoken words have always been a weapon of struggle, from the storytelling of the West Africangriots through tales of resistance told in code on the plantation so the masters couldn’t understand.

But the written word builds off these oral traditions in equally powerful ways. It allows oppressed people to communicate with potential comrades who are not immediately in their presence – and that’s crucial when they’re trying to overthrow a global system of oppression. It allows for stories of events like the Haitian revolution to spread to places like the plantations of the US South, inspiring uprisings there, even if people there had never met someone who had participated in Haiti’s revolt against slavery. Texts like Walker’s Appeal, smuggled into the US South, were powerful calls to rise up, calls that the masters needed to silence at all costs. Hence, the masters imposed illiteracy – they made sure potential rebels wouldn’t know how to read these revolutionary texts.

That forced illiteracy continues today with school systems that put a lot of effort into training students to be good capitalist workers – or future obedient prisoners. They do this instead of teaching students how to teach themselves to read. They present reading as something that is boring, dry, and whitewashed, instead of showing students how to love reading, and how to find strength in it over the course of their lives. This is especially true for Black youth, and youth who are economic refugees from the places around the world that the US dominates through its empire. As Dead Prez put it, “They schools ain’t teachin us, what we need to know to survive. They schools don’t educate, all they teach the people is lies”.

This is not an argument for abandoning struggles to defend and transform public education. As I wrote earlier, I am all for expanding the kinds of struggles teachers, parents, and students are waging, from the MAP test boycott to fights against austerity budget cuts and privatization.

However, when we say “defend and transform”, this transformation needs to confront the ways in which the school system is deeply embedded in the historical process of creating and recreating institutionalized race and class hierarchies in our society. In order to fight these, we’ll need to build spaces outside of the schools where we can learn from each other and can grow through struggle in ways that are not currently possible in public school classrooms. We can use this new knowledge to fight for better education in the classroom as well. Part 2 of Reading for Revolution makes a case for these kinds of movement-based study groups. I am currently working on Part 3, which will provide some practical suggestions and curriculum materials for how to conduct study groups.

For the full articles, please click here

Jock Culture, Rape Culture, and the need for Educator Hiring Halls

26 OctFollowing up on Veryl’s post about coaching yesterday, I’d like to share this article from the Nation about how jock culture supports rape culture, as well as this article about sexual violence at Notre Dame, my alma mater. Both report stories of young women who were raped by members of school athletic teams, and then faced terrifying retaliation for speaking out. Between these atrocities and the notorious Steubenville case, it should be increasingly clear to the public that America’s schools are breeding grounds of misogyny and rape culture, and that we need to put an end to this.

Our comrade Kloncke has written some insightful and practical analysis of the struggle against rape culture in Steubenville, emphasizing the need to seek justice outside the court systems which perpetuate patriarchy and white supremacy:

At the same time, Kloncke points out that we need to move beyond simply responding to flashpoint crises: “Support is clearly necessary, but the problem is rampant, so the danger of burnout looms large… In addition to supporting survivors of sexual assault, we must ask ourselves how to drain those stagnant pools: how to intervene in the conditions that allow rape culture to thrive.”

I agree. Education organizing and feminist anti-violence organizing should not necessarily be separate “issues”; the struggles we are waging in our schools should challenge rape culture on a day-by-day basis, as I wrote here. Kloncke lays out some suggestions for the kind of demands and goals we could fight for in our schools:

Rape culture is so pervasive that it can seem overwhelming and impossible to confront. I think Kloncke’s suggestions provide some concrete starting points for possible struggles in the schools. They highlight the kinds of demands we might be able to win if we develop our capacity and build a broad-based and militant teacher-student-community alliance.

Kloncke’s point about accountable coaches also gets at a core issue in teacher/ educator/ staff organizing that I’ve written about here. In reaction to the corporate ed reformers’ emphasis on teacher evaluation and accountability through standardized testing, a lot of Leftist and liberal teachers have fallen into the trap of trying to defend the public schools as they currently exist. This is not tenable, because our schools are breeding grounds of white supremacy, patriarchy, and class stratification. We need to transform the schools, and this means being accountable to working class communities, NOT corporate think tanks and hedge funds. Teachers and coaches should welcome working class feminist efforts to fire coaches who condone “rape crews” and to replace them with coaches who can serve as anti-sexist role models. In fact, we should join such efforts, and look for moments in our schools where we can initiate them ourselves. No amount of seniority and no union contract should protect a coach if there is clear evidence that he is complicit in encouraging rape.

As a long term goal, I think we should fight for the power to make hiring and firing decisions that affect all teachers , coaches, and anyone else who works with youth, instead of leaving these decisions up to unelected administrators. Teachers, students, and community members should be able to decide who teaches and coaches our youth. Port workers demanded and won control of hiring and firing on the docks in the 1930s, ending the racist and humiliating shape up system (similar to the process by which day laborers are hired at Home Depots today). However, over time these hiring halls became nepotistic and exclusive because they were run by the union itself as a private club, not as a public organization run by the working class as a whole. Hence workers had an incentive to try to get their brothers, sons, and inlaws onto the job, which in Seattle has resulted in discrimination against Black workers. To avoid this kind of outcome, a teacher/ coach/ education worker hiring hall would have to be run democratically with input not only from teachers but also from students and their families.

Ultimately, this would be a revolutionary demand, because it would point the way toward a society of popular councils, assemblies, and committees instead of one that is run by professional classes above society. In the meantime, we can prefigure this goal by organizing ourselves and taking direct action to push the administration to fire individual misogynistic coaches and to hire coaches who know how to challenge rape culture.

Tags: Accountability, Coaching, Corporate Ed "Reform", courageous action, Feminism, Hiring Hall, Jock culture, politics, Popular Councils, Protest, Rape Culture, Sexual assault, Sexual violence, Steubenville